With the Affordable Care Act back at the front of the media landscape as it arrives in front of the Supreme Court this week, advocates on both sides of the issue are dusting off their messaging strategies around the issue. Last Friday, President Obama signalled that rather than running from the title of “Obamacare” that Republicans have foisted upon the signature health care reform bill passed in March of 2010, he and his staff will be embracing the title.

His first move – trying to encourage supporters to adopt the #ILikeObamacare hastag on Twitter met a mixed response. Conservatives quickly attempted to co-opt the move, using the hash to discuss the reasons they dislike the bill, while others pointed out that using the hash – even to dismiss the bill – contributed to its trending success.

But this Twitter discussion is a minor squabble over a much bigger question: what are the implications of this move? Will this be a successful branding strategy, as Obama and the Democrats hope – or will this entrench opponents ever more firmly against the bill?

On the one hand, you have the Kaiser Family Foundation’s study suggesting that people really don’t understand the bill very well – and those who have more factual knowledge about the bill are more likely to support it, more likely to think it benefits their families, and less likely to support repeal. This study might bolster the underlying assumption by Democrats – if people only knew what was in the bill, they would like it more – and thus branding it as “Obamacare” might help Democrats and Obama in the long run.

On the other hand, research has suggested the bill hasn’t really benefitted Democrats so far. Research by Nyhan and his colleagues suggests that Democratic Congresspeople who supported the ACA faced an electoral penalty from voters – one that might have cost Democrats the House in 2010 (although this paper has sparked a debate – see this critique and rebuttal).

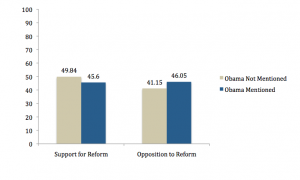

But perhaps most troubling is the research suggesting that linking Obama to the health care bill primed racial attitudes, encouraging a racial divide in feelings towards reform. Similarly, preliminary research that I’m working on with Robert Entman and Kimberly Gross at George Washington University on the polling surrounding the passage of health care reform suggests those polls that mention Obama as part of the question were seen as more negatively slanted (t=3.93, p<.001) and produced less support (t=3.41, p<.01) and more opposition for reform (t=-3.92, p<.001).

Mentioning Obama significantly decreases support for reform and increases opposition to health care reform

Therefore, President Obama’s embrace of “Obamacare” might not only hurt himself and Democrats, but make attitudes about health care more racially motivated – and thus less likely to be swayed by learning more about the bill. Further, it might also be true that Republicans have been so successful in branding the bill as “Obamacare,” that this move doesn’t really change how people think about the bill.

That said, Republicans successfully used this tactic before: during the 1993 health care reform debate, branding those efforts as “HillaryCare” as part of their efforts to classify reform as a government take-over, which Clinton health care policy advisor Paul Starr repudiates. While President Obama succeeded in getting reform passed, he is still fighting to justify his efforts and to defend the law against repeal and overturn. So while it has potential pitfalls, his attempt to own the brand and reframe the dialogue might be just what the doctor ordered.